Select a player...

Tributes to some of our favorite late friends and idols

By Dick Strobel

In the days and weeks coming, there will be much written about Edward Kleinhammer. At age 94 he lived a full life of great import, great influence and he made life better for many both inside and out of music. I invite you to share in a few of my own personal thoughts and hope that perhaps they will spark a special memory you have:

My first lesson with Edward Kleinhammer, I was 90 minutes late due to airline delay and nervous as a result. I heard full octave slurs coming from behind the north Michigan Avenue studio on the 9th floor that were unreal in their texture and sound quality. He welcomed me in. We played duets to calm me down. At the end, he looked at me and said, “Well, I suppose you want my assessment?” I did….”Poor slide, not a real solid dynamic range, not a real solid tonal range. Not pleased with your tonguing. Intonation is inconsistent. You don’t sight read very well. Rhythm is iffy.

But you know, I don’t worry about that stuff too much. You demonstrate a musical heart and an expression that are wonderful. We can fix the rest. So… are you ready?” Ed was a man always to the point, but never negative. There was always an upside to every comment.

I was there when Ed’s first wife passed away. We played the Mozart Requiem back and forth. Again and again. I don’t think we talked ten words the whole time.

I was with Ed when he was prepped to leave for Iceland, a personal trip, not part of the orchestra. A trip, he said, to match his heart. It was, “hard to be alone.”I was with Ed after he returned from a trip to the Northwest (I believe it was along the Gunflint Trial in Minnesota) and his story of meeting a bear. He said he wasn’t nervous, but did shine the club he held in the bear’s face, and was ready to swing at it with his flashlight. We laughed at that story. He never said what the bear did.

A Saturday morning at Ed’s studio. Pliers, screw driver, black tape, an old bass clarinet key, and one of my Wife’s elastic hair ribbons. We take apart the side-by-side triggers on a double valve horn, clamp the clarinet key to the side and hook the hair ribbon in place. Ed said, “ Ok, let me try it first.” For the next hour, Edward Kleinhammer played all the great excerpts for the horn one after another. I was enthralled. He was like a kid in a candy store. “Ok, now you try it.” I did. At the end, we looked at each other and agreed, we had a side trigger for the second valve. Ed had a gleam in his eye. “It’s better.” In California they were cranking them out in shops everywhere, and years later , Schilke would make a professionally done rig for him, but for Ed and I, it was our first, and one we made ourselves.

I was there when one of Ed’s fellow section mates mentioned the story of the “light pole incident.” Had I heard the story? Ed, listening to this, turned white and said, “ I’ll deny it. Don’t tell him about that. Who spilled the beans? It was Jake wasn’t it? Or Scarlett? Who was it?” He never focused the rest of the luncheon. At my next lesson, I was curious but he wouldn’t own up. He told me that story was all a joke, not true, he had nothing to do with it, and it never happened. The incident itself was never the focus, it was always Ed’s reaction that made the story and spawned a lot of good natured fun (at his expense) in its day.

I was there on an Easter when there came a knock on the door of his studio. Ed opened it to find a mute bag full of hard boiled eggs and my Wife Valory at the corner giggling. She scampered away and I watched Ed chase her all the way down the hall to catch her and plant a kiss on her cheek. Edward Kleinhammer at a dead run. It was sight to behold. During the rest of the lesson, I worked on Bruckner to the steady crunch of shells next to me. By the time the lesson ended, the mute bag was empty and the wreckage of egg shells littered the floor. Ed liked eggs.

Ed called from the Elkhart Bach factory. “ I think I have a horn for you. Shall I bring it back?” Lloyd Filio had talked Ed into trying this particular horn out. It was purchased through Giardinelli in New York and I paid Ed $265 at my next lesson. When I played it for the first time, he said, “I knew this ax was you from the first note played.” It was.

We finished a lesson and Ed said, “come with me.” We went to Shilke’s shop and viewed the valve section Reynold Schilke was building for Ed for his first “true double valve,” bass trombone. He had high hopes for it, but worried it would be too heavy. Ed had a Bach bell mounted, then changed to an Earl Williams bell. I played the second bell by Ed’s locker at Orchestra hall for him after a rehearsal. He looked at me and said, “ the Williams is better.” I often wondered how many other players he asked to play his horn for him. I never found out.

The first audition: I called him at home at 11:55 p.m. on a Thursday night. He answered on the first ring and said, “You won.” When I said yes, he laughed. “ Atta boy.” We talked until close to 1:00 a.m. It had been my first professional audition win and he knew the results before I ever said a word. He never said my call was perhaps coming a bit late at night, he just listened and enjoyed my excitement.

Christmas: We played Silent Night, Holy Night, in duet form, changing keys, changing registers, on and on and on, just not wanting to stop. He said, “It’s the music. Its why we are here.”

Max Bonecutter won the Minnesota audition. Ed was proud for Max. To me he said, “You see? Max was ready. When you are ready, you win. Max practices like he is auditioning and auditions like he was practicing…now its your turn. You have to be ready.” Ed didn’t look backwards. He was always looking ahead, always to the same goal: To being just a bit better today then he was yesterday.

Ed had a hammer and was hanging a small plague on the wall of his studio. He pointed to it. He said, “the members, they vote. Isn’t that something! They say that about me.” The plague said, “Edward Kleinhammer, Best Musician of the Year. The Chicago Symphony.” He was proud of that accolade, but also challenged by it. He would tell me he read that every day he walked in to his studio. A reminder.

A Mahler 2nd symphony Chorale lesson. Ed looked at the floor, his hands down. “You know you have more in you than you are letting come out. Don’t hide your candle. Do this: Think of the man who woke up this morning, sick. He gets up and finds the house empty. His Wife gone. A note on the table: ‘I am leaving you.’ He goes to work: ‘We are laying you off.’ He walks the streets, lost, suffering anquish at how awful life has become. There is nothing but misery. He walks into an open building, a strange place, a large hall, many seats. He collapses down on a chair. On stage you sit, alone, playing quiet tones on your bass trombone, warming up. Each note is a thing of beauty. Each is a symphony of its own. Each imparts the love you have for what you do with that piece of brass you hold. The man sits and listens. He doesn’t know what you play, or how you play it, or why. He justs hears its simple beauty…For that moment, you—and only you– have made his life, just a little bit better.

Dick, I call that my ‘key-hole peak into heaven.’ When I can impart my sound on my horn– that way– and make one person’s heartache depart for a time, and hear the glory that is in life, it is, for me–my key hole peak through the door into heaven. Someday, I hope to push that door open–even if just a crack.” One small tear, quickly brushed away.

The door is wide open for you Ed.

To learn more about Edward Kleinhammer, read Doug Yeo’s post on the 100th year to the date of Edward Kleinhammer’s birth. Doug was Kleinhammer’s student and the man Doug credits with changing his life.

By Bob Weller

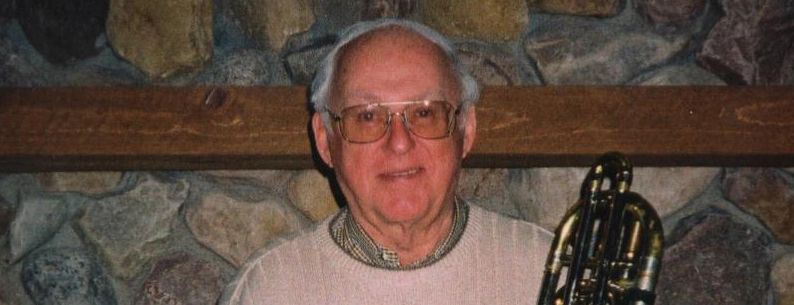

There have been several great musicians who that have helped develop the art of being a bass trombonist. Edward Kleinhammer, Charlie Vernon, Doug Yeo and David Taylor are just a few of the names that are well known but the man that brought the instrument to the forefront is George Roberts.

George’s sound, style of play and musicianship has left an indelible imprint on bass trombonists both young and old.

Paul Hill did a wonderful interview with George a few years back. Take a few minutes to read the interview at this site.

http://www.trombone.org/articles/library/viewarticles.asp?ArtID=257

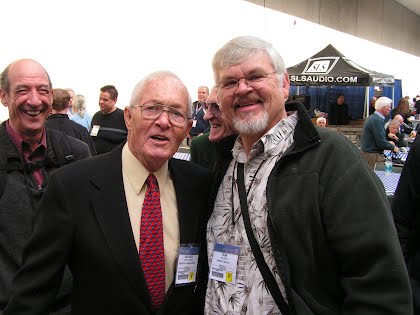

It is always a treat spending time with George. What a fine person not to mention a fantastic bass trombonist!!

By Michael Lake

The great friend and member of Bones Southwest, Bill Tole passed on May 20th.

Bill had a great career, and one that not many trombonists experience. Bill came from a musical family. His father was a music teacher who played trombone and piano, his mother also played piano, and his brother was a Los Angeles studio musician.

Immediately out of college, Bill auditioned for the Tommy Dorsey band. Winning the audition, Bill went on tour with the band for several years. Shortly thereafter, Bill became principal trombonist, soloist and co-leader for four years with the Airmen of Note.

Bill next moved to New York City in the mid 60’s and played for many of the top Broadway shows, worked club dates and kept busy doing recordings in the studios. A change in the studio scene relocated Bill to Los Angeles in 1967 where he continued recording on albums, commercials, television and movies. Bill’s career took a different turn when a producer put out a casting call for a trombonist to portray Tommy Dorsey in a film starring Liza Minelli and Robert DeNiro. In Bill Tole they not only found a professional trombone player who understood the musical era and who had a big band of his own for the movie, but someone who could play as sweet as Dorsey. Tole had the musical credentials to land the part, and looked just like that “sentimental gentleman” in the 1977 release New York, NY.

Bill Tole as Tommy Dorsey in the film New York, New York

My personal experience with Bill Tole came shortly after I returned to live in Phoenix. A friend had suggested I attend a rehearsal of a band that needed a trombone. The band was the MCC “Red Mountain” band and the lead trombone was none other than Bill Tole. What I remember about Bill was how kind he was in letting me play some lead charts and solo. He was a true section leader in helping me navigate charts and providing expert musical guidance to me and the rest of the trombones.

Since then, I had the honor of playing occasionally with Bill, and what I always found was a kind and gentle man who played wonderfully and who never uttered an unkind word about anyone.

Bill Tole will be missed not just for his silky smooth trombone tone and vibrato, but for his honest benevolence toward all with whom he came in contact. He also serves as a reminder to trombone players and others that it is entirely possible to play the role you were born to play and do so over an entire long career.

By Michael Lake

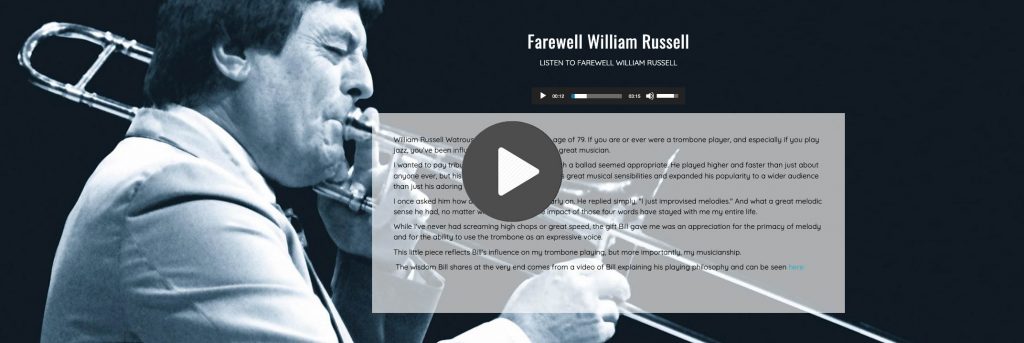

William Russell Watrous recently passed at the age of 79 on July 2, 2018. If you are or ever were a trombone player, and especially if you play jazz, you’ve been influenced in some way by this great musician.

I first me Bill when I was in college. He was a friend of our jazz Director who asked him to town for a few days of masterclasses and concerts. I was the chosen one to pick Bill up at the airport and chauffeur him around. That was a great gig for me because I was able to ask him lots of questions about trombone and playing professionally. He was very kind, and he obviously loved talking to your enthusiastic trombone players.

I’d seen him around through the years, but in 2017, I got to play with him again. The 2017 International Trombone Festival had jazz night on the last night of the event. The headliners were Dick Nash, Bob McChesney, Scott Whitfield, and Bill Watrous.

I had great fun that night listening to these great players and then getting the opportunity to play something for this room full of trombone enthusiasts. The other highlight of that evening was arriving back at the hotel just as Dick Nash walked in. Dick came up to me looked up and said, “Kid, you played your ass off tonight.”

When Bill passed, I wanted to create some sort of tribute to him and I felt inspired to write a ballad I called Farewell William Russell.

Bill played played higher and faster than just about anyone ever, but his ballad playing brought out his great musical sensibilities and expanded his popularity to a wider audience than just his adoring trombone fans.

I once asked him how and what he practiced early on. He replied simply, “I just improvised melodies.” And what a great melodic sense he had, no matter what he played. The impact of those four words have stayed with me my entire life.

While I’ve never had screaming high chops or great speed, the gift Bill gave me was an appreciation for the primacy of melody and for the ability to use the trombone as an expressive voice.

This little piece reflects Bill’s influence on my trombone playing, but more importantly, my musicianship.

The wisdom Bill shares at the very end comes from a video of Bill explaining his playing philosophy and can be seen here: